Federal Policy and Racial Inequity (Part 1)

This is the first of two parts on housing policy and structural wealth inequalities in the United States. I’ll write part two next week, and likely will be returning to the theme often. Today I’m giving a brief history of how policies in the mid-twentieth century operated on Black communities. Next week we’ll look at the contemporary legacy they’ve left.

Over the past six months I’ve been spending a lot of time reading up and trying to learn about how federal housing policy in the mid-twentieth continues to shape a lot of current racial inequalities. It’s a big, hairy, complicated history, and I’ve been waiting to write anything about it here until I got my hands around it a little bit more. I’ve realized, though, that if I wait until I COMPLETELY UNDERSTAND systemic inequality I’ll never write about it at all. Also, Matthew Desmond came out with a piece in the Times yesterday touching on these issues. His book Evicted played a role in thinking all of this through, so his article served as a call to action. This is likely a topic I’ll be wrestling with a lot in this space, so consider this the beginning of an ongoing conversation. I hope you’ll join in.

Late last year, I returned to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ bombshell of a piece from June of 2014 in the Atlantic, The Case for Reparations. If you haven’t read it, I really really recommend you set aside a half hour and make your way through it. I know that I often say “this great piece” or “that great piece”, but Coates’ article is a foundational piece of work for me and, by extension, this blog. Coates walks through the history of redlining and housing discrimination in Chicago. Redlining was something I’d heard of, like everyone, but I didn’t know a whole lot about it. Simply put, local and federal policy completely fucked the Black community in Chicago. (That’s a strong word, but strong words ought to be reserved for and strategically deployed in wildly egregious circumstances. There aren’t many situations in which I’d use “fucked” on a public forum like this, but this is one of them.)

During FDR’s New Deal, the market for mortgages in the United States changed dramatically. Prior to the Great Depression, mortgages generally required hefty down payments, and banks demanded repayment within 10 years. It wasn’t until the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created in 1933 and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) the next year that our modern mortgage structure was born. Loans with small down payments that could be amortized over 20 or 30 years became the norm. This was not, however, an example of the free market extending into new lines of business. It was actually a publicly subsidized insurance program – HOLC and the FHA insured mortgages issued in neighborhoods they considered safe for investment. This public insurance dramatically lowered the cost of a mortgage. The program became especially widespread following World War II and the the roll-out of the GI Bill, and ultimately spurred vast new residential construction. Because this insurance was effectively a subsidy for home ownership, it set in motion a trend away from renting that continues today. As we’ll see next week, that trend is further cemented by the biggest loophole in the United States tax code.

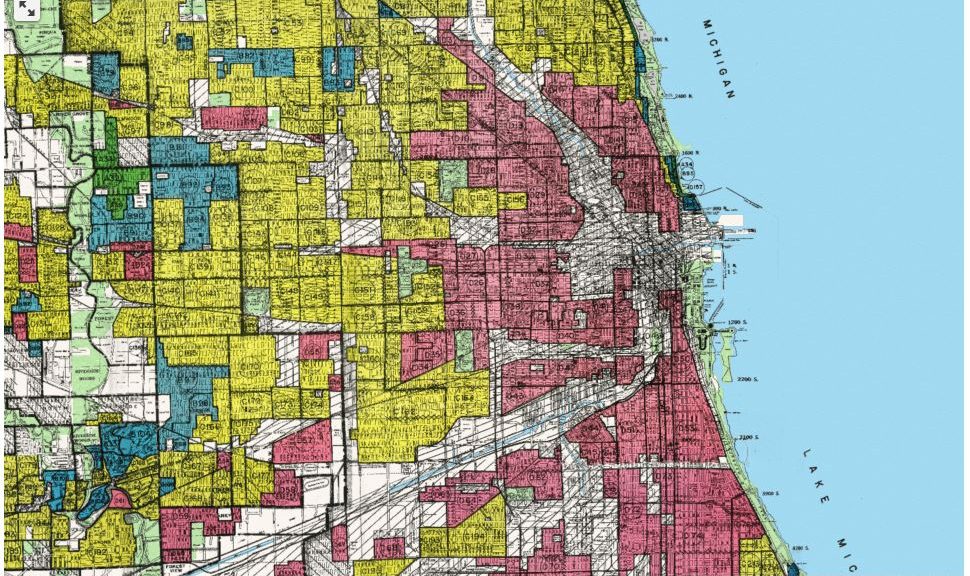

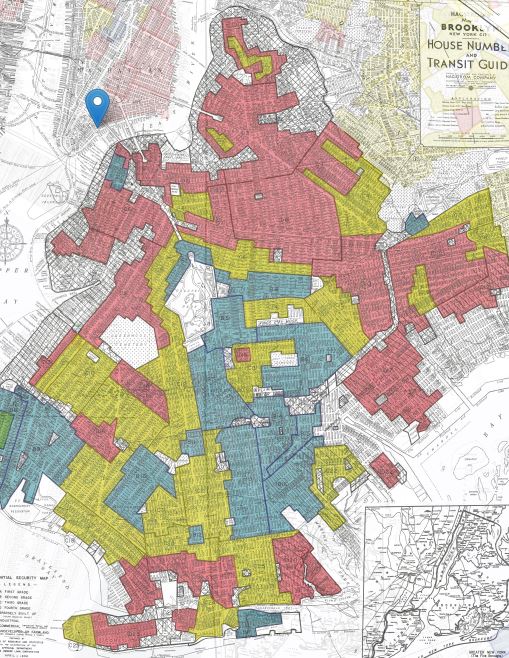

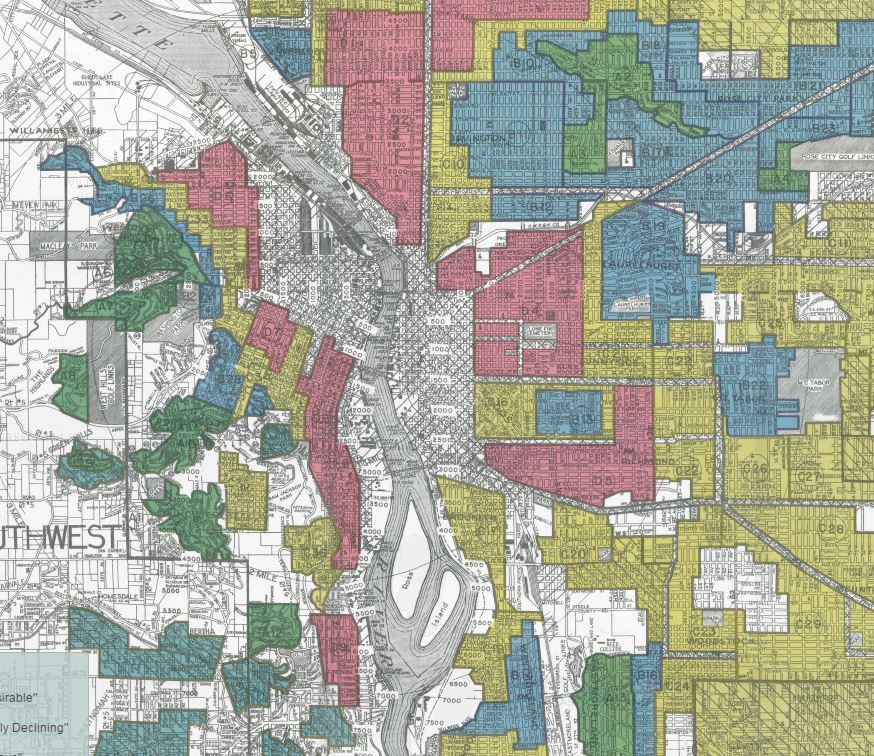

The term redlining comes from the maps drawn by HOLC where they laid out the neighborhoods in which they were willing to insure mortgages. Green areas were considered very safe and received automatic mortgage insurance. Red areas were automatically denied. Because lending under the insurance program was especially lucrative, private lenders shifted the vast majority of their mortgage activity into these green neighborhoods. As a result, mortgages were impossible to obtain in red zones. Here, for instance, is a map of Brooklyn from the 1940s:

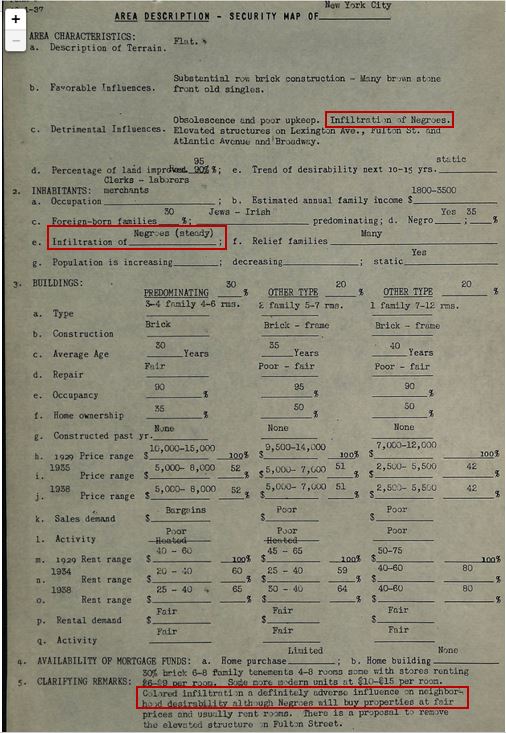

Bay Ridge is the only area (in the center left, green) to receive top marks for investment stability. Why was one of the biggest residential areas in the country considered unsafe to receive federally subsidized loans? The paperwork from my neighborhood offers a clue:

“Infiltration of Negroes.” “Infiltration of: Negroes.” “Colored infiltration is a definitely adverse influence on neighborhood desirability.” Keep in mind that these aren’t documents from some bank looking to make a profit – they come from the federal government, generations after the Emancipation Proclamation.

This is the case throughout Brooklyn – black folks were moving in, so the FHA refused to lend to these areas. The FHA’s rationale for refusing to lend in Black neighborhoods is a good example of how complicated issues of race can be. The FHA considered these neighborhoods unsafe for investment because when Black families moved into a neighborhood property values often fell, leading to trouble for lenders. Of course, by refusing to lend in neighborhoods where Black families moved in, the FHA set in motion a self-fulfilling prophesy: an inability to get a mortgage reduces demand, leading to lower prices. The FHA structurally caused home prices to go down in Black neighborhoods, then pointed to the results of their actions as justification for them.

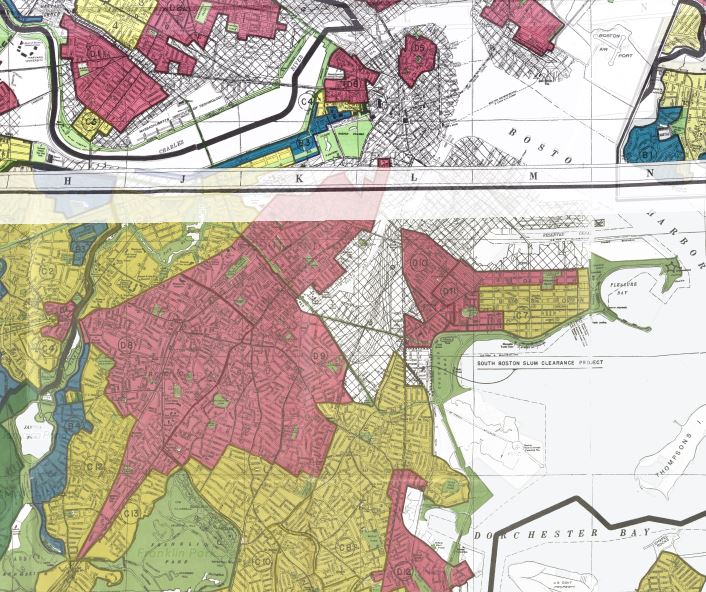

The ghettos where Black families were penned in by an inability to get mortgages look starkly similar to residential distributions today. The residential distribution of cities I know well continue to be dominated by the patterns codified by the FHA nearly a century ago:

Boston

Portland, Oregon

Use this tool to take a look at whether or not the patterns in your city and cities you know well follow these trends.

The federal government systematically undermined any incentives to lend money in Black neighborhoods. This meant not only that African Americans were unable to receive financing for home purchases, but also that they were unable to use leverage the lending market to make needed repairs for their homes. Black communities tended to be in older parts of cities – areas in need of financial investment. Because of the federally-sponsored unwillingness of banks to lend in these areas, they fell into greater and greater states of disrepair. This trend has continued until today. Poor areas are unable to secure financing that would allow small businesses and land owners to improve their districts, leading to worsening states of repair. Those who can leave do, and the cycle continues.

If the banks were unwilling to lend in these majority Black neighborhoods, why didn’t upwardly mobile Black families simply move into whiter areas where they could receive financing? There were, of course, enormous social barriers to such a move. Much violence was directed against Blacks looking to move into white areas, and Black folks, like people everywhere, were disinclined to move out of their communities. There were also, however, two powerful legal tools used to prevent such a move. The first was the FHA mapping itself. While Black families could look in FHA approved areas, the potential presence of a single Black family on a block could lead the FHA to refuse mortgage insurance – meaning, effectively, that the red lines followed them wherever they went (Milton’s Satan – “which way I fly is hell” – comes to mind).

Not only were Black community members systematically denied the opportunity to buy homes using mortgages, they were equally unable to rent or buy without a mortgage wherever they wanted thanks to what were called “restrictive covenants.” Restrictive covenants were often written into a house’s deed, dictating that the purchaser not rent or sell their home to Black individuals or families. Even the Black families wealthy enough to buy homes without mortgage assistance were entirely barred from most neighborhoods in the city because of restrictive covenants. They were forced to rent or buy in crowded, all Black neighborhoods. It should come as no surprise that these neighborhoods were systematically underfunded, receiving little public infrastructure or public spending. Although the Supreme Court outlawed restrictive covenants in 1948, local municipalities continued to allow these illegal clauses for decades thereafter – the birth and sustaining force of the so-called “inner city.”

If you’ve spent any time around me this year, you’ve heard me talk about a book called Family Properties by Beryl Satter. Satter’s father represented Black folks pushed out of the mortgage market and into a products known simply as “contracts.” These were the only way Black families could reach toward home ownership, and they paid for their homes on an installment plan. Importantly, they built up no equity until they had completely paid for the home – and sellers often charged the Black buyers with false infractions after they had nearly paid for the home, voiding the contract and causing would-be home owners to lose all the money they had paid. Satter catalogs how the worst of these contract sellers would “sell” the same home over and over again, cheating countless families out of their savings.

There was also an element of simple supply and demand at work. Because Black families were not allowed to live in most neighborhoods thanks to restrictive covenants, home and rental prices in the few areas they were allowed to live went through the roof. Similarly, landlords had little incentive to keep their buildings in a state of good repair, knowing their tenants could hardly leave for a new building. Isabel Wilkerson sums up the result in her incredible, Pulitzer-winning, The Warmth of Other Suns:

The story played out in virtually every northern city- migrants sealed off in overcrowded colonies that would become the foundation for ghettos that would persist into the next century. These were the original colored quarters- the abandoned and identifiable no-man’s lands that came into being when the least-paid people were forced to pay the highest rents for the most dilapidated housing owned by absentee landlords trying to wring the most money out of a place nobody cared about.

The FHA no longer allows mortgage discrimination based on race and the Supreme Court struck down restrictive covenants in 1948. Though illegal, both these programs continued under various guises. But even if federal policy had successfully ended all discrimination in the housing market in the last century, Black families would still be feeling the repercussions today. White families built up tremendous amounts of wealth in the Post War period thanks to help from the federal government not given to their Black neighbors, and that wealth was passed down from one generation to the next. As we’ll talk more about next week, a straight line can be drawn from the policies of the Post War period and current wealth income inequalities today. Today, white households headed by someone with a college degree have a median wealth of $301,300. College-educated Black households? Just $26,300, less than 10% that of their equally educated counterparts. Even when controlling for education and income, the wealth gap is staggering. And much of that is due to the choices we’ve collectively made and supported surrounding housing policy in this country.