Housing for the Homeless

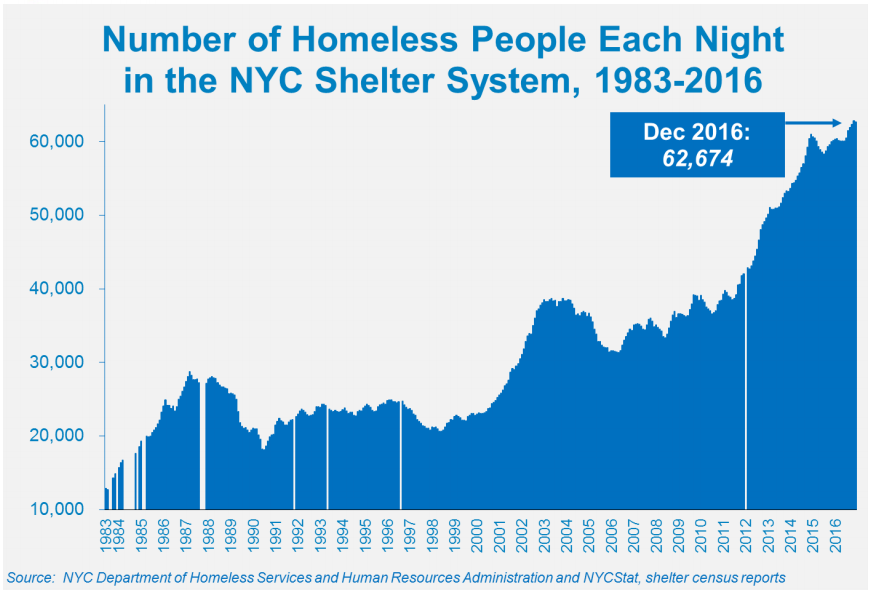

Over the course of the past year and a half the issue of homelessness in New York has been growing more and more visible to the public eye. According to coalition for the homeless, 2016 saw the highest level of homelessness in the city since the Great Depression. While the population of the city has obviously grown, the growth in admittance to city run shelters is truly sobering:

As the issue has grown, so too have the political ramifications for a mayor who centered his 2013 campaign on a “Tale of Two Cities,” vowing to fight an increasing divide between the increasingly wealthy folks pouring into the city and poorer communities. In September of 2015, deputy mayor for Health and Human Services (the main agency overseeing homeless services) Lilliam Barrios-Paoli resigned, and was quickly followed by Department of Homeless Services Commissioner Gilbert Taylor quitting abruptly in December of 2015. In November of 2015, in response to a call from de Blasio for the state to “step up” and help shoulder some of the costs associated with homelessness, an aide to Governor Cuomo took a shot at the mayor in the press by telling the Daily News “[I]t’s clear that the Mayor can’t manage the homeless crisis” and suggesting that maybe de Blasio isn’t smart enough to solve the problem. While we’ve all come to expect the perpetual pissing match between our dearly beloved mayor and governor, this exchange was particularly pointed. In April of last year, the report summarizing the state of homelessness ordered by the mayor was released. This report brought together staff from City Hall, the Human Resources Administration, the Department of Homeless Services and the Mayor’s Office of Operations to systematically examine why things had gotten so out of hand. Out of this report grew the current proposal to build 90 new shelters around the city.

All of this, of course, has taken place against the broader discussion of the city’s role in promoting housing development. From the conversation surrounding the renewal of the 421-a program (which provides tax incentives for building on vacant or mostly vacant land in the city) to last spring’s drawn out battle surrounding Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (a program requiring developers to designate a certain percentage of their units as affordable for a fixed amount of time), to the wildly popular new blog Think Urbanism, it seems like all anyone is talking about these days is housing (or maybe that’s just what I read?).

What, then, is the immediate backdrop behind the current situation? New York City is under legal requirement to provide a bed for anyone who enters a public shelter looking for one. When there are no available beds, families are generally put up in motels around the city. As the homeless population has risen much more quickly than shelter beds, the result has been an enormous increase in the cost to the city – the Times reported last month that the City spends around $400,000 a day on hotel rooms. Moreover, the rise in homelessness that has bedeviled the mayor for the past three years will almost certainly be used against him as his campaign for re-election this fall ramps up. It’s no surprise, then, that the de Blasio administration is making this push now.

I’ve been following the conversation with interest because one of the most strenuously opposed shelters is supposed to open this week two blocks from my apartment at 1173 Bergen Street. Whether or not it will in fact open is unclear at this point due to community opposition [UPDATE: The opening has been indefinitely postponed]. As Gothamist reported last week, the shelter is supposed to have 100 beds reserved for men over the age of 62. The building, nestled among the Brooklyn brownstones, wasn’t being used for anything prior to its renovation. But the backlash against this shelter raise much more interesting questions than the anger directed at the proposed shelter in Maspeth last fall. The neighborhood of Maspeth, Queens, had no shelters when the mayor proposed the siting last fall, despite the fact that around 250 people from the neighborhood lived in city-run shelters outside the neighborhood. The conversation was characterized by classic NIMBY (“not in my backyard”) lines such as the anonymous resident assuring the local reporter, “We’re not against homeless people, we’re just against where the shelter is.” Whether or not you find their story sympathetic, it was hard to deny the fact that this community wanted to keep the unhoused folks “over there” – anywhere but Maspeth. Maspeth residents were ultimately successful in their fight to keep the shelter out.

Crown Heights, however, is different. As the Daily News reported earlier this month, Brooklyn’s Community Board 8 (in which the Bergen Street shelter is located) already has 679 homeless beds. This figure is far higher than neighboring Community Board 6 in Park Slope. CB6 (the mayor’s neighborhood, current residence at Gracie Mansion not withstanding) has just 267 beds, despite having roughly 10% more residents. Community Board 8 sits in an area that was historically red-lined, is 67% black, and has a poverty rate of 26%. Community Board 6, on the other hand, is 75% white and has a poverty rate half that of Crown Heights. The concentration of existing shelter beds, minority population, and poverty have led to understandable claims that the neighborhood has become a dumping ground for the unhoused. Moreover, as Nikita Stewart explained earlier this month, the current plan “runs directly counter to a new City Council effort to strengthen the Fair Share Law, aimed at equitably spreading social service and other programs and amenities around the city.” (To be sure, CB6 is not the neighborhood with the lowest level of shelter beds, nor is Crown Heights the highest – though their adjacency does make the discrepancy jarring)

On the other hand, the City has argued that as they site the new shelters, they are looking at placing them in the districts experiencing the highest levels of homelessness and poverty. The thinking behind this is simple: people (in the case of the Bergen shelter, senior men) should have the option to have shelters in their communities. These guys likely have friends and family in the neighborhood, and one can make the argument that siting shelters in these districts respects the existing community. These ties could also lead to informal dissemination of job opportunities through casual interaction. The well-known but unremarked-upon secondary fact is that property tends to be less expensive in these areas, leading to a lower cost per bed – something that should be taken into account.

Unfortunately, the City has put the neighborhood in an impossible spot. They either complain about the location of the new shelters and come across as heartless, or they simply allow the City to assume that there will be less resistance to unpopular policies in poorer communities of color. Luckily, the press has distinguished this case from the case of Maspeth last fall and largely refrained from casting Crown Heights residents as NIMBYs. Indeed, while residents are currently pointing to the discrepancies in the locations of the shelters, calls for reductions of current shelter beds are muted. The current debate is centered not on whether Crown Heights ought to have any shelter beds, but rather about the inherent fairness of concentrating homeless shelters in historically marginalized communities.

This is a tough one for me. On the one hand, the idea of a homeless shelter down the street doesn’t bother me at all. In fact, my system of ethics compels me to provide shelter for the unhoused without reservation, so resistance to a shelter at any level is uncomfortable for me. On the other hand, to ignore the historical complexities of the issue would be a mistake. Traditional public housing projects have often failed in the past in large part because the concentration of poverty in a particular district prevents the formation of social ties that can often lead to better opportunities for lower income folks. Furthermore, much of the current concentration of poverty in minority areas can be directly traced to racist housing policies employed by the federal and local governments. To now say that these neighborhoods are alone responsible for dealing with the results of those policies is wrongheaded and cruel. What’s more, the willingness of the City to back down from the introduction of a single shelter bed in Maspeth (a whiter and wealthier area than Crown Heights) means that any imposition of the current plan over the objections of residents becomes, rightfully, much more loaded. So, while I do want the City to continue to build shelter beds, I have to agree with my neighbors that the placement of this shelter is ill-advised. The City ought to be taking current beds and historical factors into consideration when siting shelters. If, however, 1173 Bergen does open as a shelter to senior men, I look forward to chatting with them on the stoop, hearing their stories, and welcoming them to our neighborhood.