Governmental Competition and the Enfeebling of the City

The city almost seemed to proclaim a right to happiness and pleasure, even for people insignificant in terms of wealth and power. That was the promise implicit in the ordinary, everyday monuments of the local health clinics, the free museums, the affordable transportation: a right to belong to the city and to have the city belong to you.

Kim Phillips-Fein, Fear City

The last two weeks were finals season for the spring semester at NYU, which meant one thing – I had free time to read real books instead of classwork! Now that the summer term has started back up, I’m back to sneaking in reading where ever it fits, finance textbook notwithstanding.

One of the books I read was called Fear City, which came out in April and was written by an NYU historian named Kim Phillips-Fein. In it, Phillips-Fein takes a new look at the fiscal crisis faced by New York City in the 1970s and explores how the outcome of the crisis has continued to dictate the ways in which municipalities, states, and countries respond to a lack of funds. What happened in NYC 40 years ago colored Detroit’s bankruptcy, the Eurozone’s relationship with Greece, and the current crisis in Puerto Rico.

From the mid-1960s through the early 1970s, the financial situation of New York City deteriorated rapidly. Though papered over by the continuance of the Post War boom, fault lines were being drawn throughout the public sector thanks in large part to the same things causing stresses throughout urban America at the time. White flight meant that many families of means were decamping for the suburbs. This movement for the well-off was aided in no small part by the mortgage interest deduction (artificially lowering the cost of home ownership) and Eisenhower’s interstate highway program whose legacy continues to haunt us today. Moreover, as manufacturers began the decades-long shift toward suburban and overseas productions, the economic engine for middle- and working-class employment began to sputter. All it took, then, was the recession that began in 1973 to push New York into a true fiscal crisis.

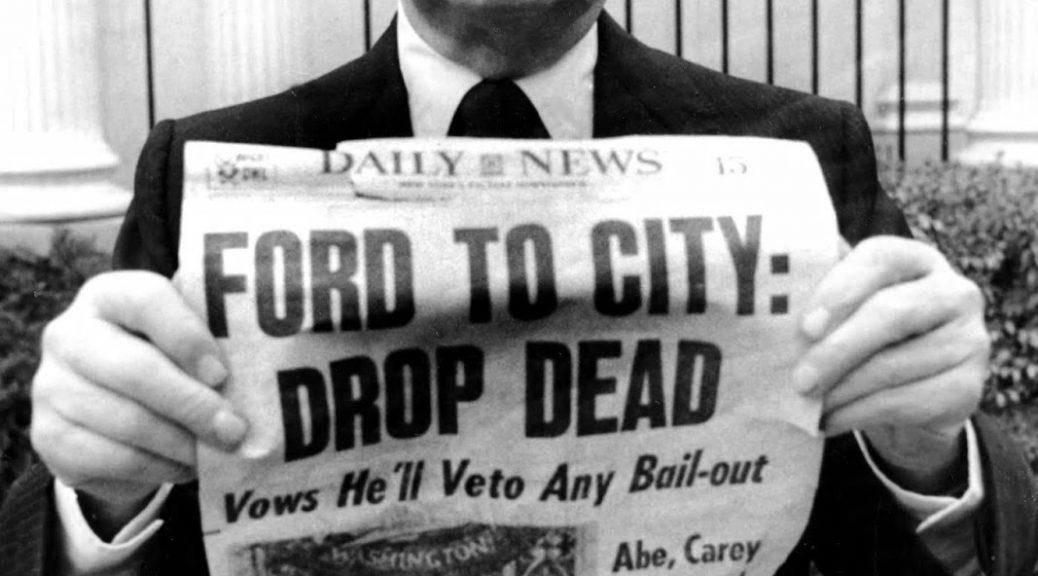

Phillips-Fein does an excellent job telling the story of how the city avoided filing, technically, for bankruptcy through some techniques that were later declared unconstitutional (the city stopped paying interest on some of its debt for a year, though eventually made the creditors whole). There was high drama as the Ford Administration (and, later, the Carter Administration) refused to make federal aid available to the city in order to avoid bankruptcy, culminating in the now-infamous Daily News headline pictured above. Rather than recognize that New York City was part of a nationwide system, the federal government acted as though New York was responsible for its own ills. In reality, many of the newly arriving poor were Black families fleeing discrimination in the South – a situation New York clearly didn’t create. To deny aid to New York City as it dealt with symptoms was to deny the interconnected reality of governmental bodies below the federal level.

What Phillips-Fein doesn’t spend nearly enough time developing, in my opinion, is why the city ended up near bankruptcy to begin with. We’ve spent a lot of time talking here about the environmental and social problems associated with suburbanization, but Fear City has me pondering the fiscal implications. Reading Fear City in isolation would leave the reader thinking that the debt service (IE, the interest paid on money loaned to the city through bonds) was the major problem. If only the debt could be forgiven, she seems to imply, the city would have had no problem continuing to provide the same level of service it always had. The heart of the crisis lay not in a mismatch of tax receipts and public spending, but rather a rapacious bond market demanding exorbitant interest rates.

To be sure, this was a huge part of the problem. Between 1965 and 1975, the portion of the budget dedicated to paying interest and repaying investors ballooned, threatening to crowd out all other spending. Phillips-Fein does a really great job describing the decisions facing the city and how they grappled with a shortage of funds. During the 1970s, the city effectively broke its contracts with city employees to avoid breaking its contracts with bond holders. Economic orthodoxy calls this the prudent decision, but Phillips-Fein questions the validity of this approach in a real smart way. The city, she argues, was going to fail to uphold its obligations to some stakeholders. Why, she asks, should city employees bear the risk of a financial shortfall? Doesn’t the city have a greater obligation to its residents, through payment of public employees and the services provided to residents, than it does to far-flung investors? And don’t investors explicitly assume this risk when they buy an investment product? Phillips-Fein glosses over the more technical aspects of municipal finance: capital projects often must be financed using debt, and if the city defaulted on its loans it would likely be unable to finance any new major public investments. Despite this omission, however, Fear City manages to underscore that a city makes many types of contracts – and that it’s improper for a city to immediately assume that bondholders are the most important stakeholders in a city.

However, to focus on whether the city ought to have repaid bondholders or maintained city payrolls misses the more important conversation. For all the weight that interest repayments had on city finances in the 1970s, a more pernicious reality was at hand. Even if all of New York City’s debt had been forgiven, the city wouldn’t have been able to cover its costs. In other words, even ignoring debt service and repayment, the city spent more money each year than it received in tax revenue and state and federal support. This fact was the true heart of the fiscal crisis. As we’ve talked about before, the post-War period in the United States was characterized by a massive de-urbanization. Automobiles, cheap mortgages, and an influx of Black southerners all pushed whiter, wealthier families out of the city. Income and property taxes, of course, left with them. Even as poorer people were arriving in the city, attracted by a robust safety net and good public services, the wealthy were fleeing.

What happens when wealthy people leave a municipality even as poorer people move in? Finances fall apart. The tax base is eviscerated at precisely the moment when more people are coming to rely on aid, which means that expenses go up while revenues go down. To use the insurance analogy, it’s similar to healthy people choosing to stop buying insurance right when a major disease outbreak hits. Simply put, the system collapses. While there are many reasons people choose to sort themselves along racial and economic lines, there’s no good reason that people moving from one part of a metropolitan region to another could cause the city to collapse – no reason except for the fact that capitalism has left its good and proper place in the private sector and sneaked its way into our governance systems, too.

As any reader of this blog knows, I think capitalism is great. I believe that it has a tremendous capacity to deliver societal good. I also think that we need strong governmental oversight to ensure robust competition through strong anti-monopoly laws, a significantly higher minimum wage and stronger unions to ensure an efficient return to labor, and policy to counteract negative externalities such as environmental degradation that the private market is incapable of pricing correctly. An idea I’m playing with right now that I’ve never really thought about before is whether or not we should be promoting competition between states and municipalities.

On the one hand, this competition can produce public benefits. If one city wantonly spends tax dollars on pet projects, or if its politicians corruptly pocket profits, citizens will obviously leave. On net, however, I’m coming to think that for all the good competition creates in the private market, competition between municipalities creates far more negatives than positives. The fiscal crisis in New York City is a great example. In the 1970s, wealthy people moved from the city to tony suburbs. Through policies such as minimum lot sizes (ensuring only people wealthy enough to buy a certain number of acres could live there) and racially restrictive covenants, these cities could exclude poor people from their borders. These suburban insurance pools effectively exclude the high risk individuals. The people who can leave, do. They know that if they move out of New York City, for instance, they can stop paying the city income tax. The city, then, is left with the responsibility to pay for the social services of all those excluded from the suburbs without tax revenue from any of the high incomes and high spending.

Why did cities in the early and mid-twentieth century look so much different than they do now? How were we able to marshal the resources necessary to build the great capital infrastructure of the last century, from water mains to subway line? It was because, when suburbs weren’t competing with one another for residents, the rich and the poor alike lived in the city itself. The city, an enormous political body, was able to draw on the tax receipts of residents wealthy and poor alike. As residents moved to any number of tiny suburbs, the capacity for planning at a regional level was frittered away. No longer could the central city finance major projects that benefited the entire region, because it no longer commanded the same resources. Many cities, such as New York, fell into fiscal crises when the region expected it to continue to play the same role on a shrunken budget.

This self-removal from the city’s tax base is even more problematic when the city itself is the major employment center for the metropolitan region. Suburbanites receive tremendous economic value from the city via their employment, but manage to avoid paying for those benefits when they return home to their low-tax, suburban homes. Forget your welfare queens – the real moochers are the high income folks who could afford to financially support the city from which they draw value but choose not to. When we focus on using the tax code to attract employers to the city and then watch as their employees live outside city limits, we tell our big cities they need to subsidize non-residents.

If the fiscal crisis in New York City taught us anything about the difficulties of financing municipalities, it’s this: the unit of governance for metropolitan areas should be the metropolis, not the city. While competition makes sense in the private market, competition among municipalities within a metropolitan area ensures a sub-optimal outcome. The result is not so much a free-market idyll of a collection of efficient firms, but rather a single firm in which some departments hoard excess resources desperately needed in others. This ensures not only high levels of geographic segregation between different incomes, classes, and races, but it also means that even within a single, interdependent population high income folks are able to avoid paying for the services they use, while lower income people are a captive market.

Until we recognize that we actually live in metropolitan areas, not efficiently competitive and arbitrarily incorporated towns, our greater metro regions will continue to be marked by high levels of inequality. Indeed, the entire program of suburban incorporation, as opposed to the older model of annexation, springs from suburbanites who wished to benefit from the city without shouldering their costs. Is a metro-wide tax policy politically feasible? Hardly. But until we seriously acknowledge the problems caused by the Balkanization of our metropolitan regions, any attempts to address inequality or ensure that region-wide economic growth has a broad base and is sustainable will be a waste of time.