Summerhill: Selling Urban Failure

I’m a gentrifier.

I say that without self-flagellation or condemnation, but merely as a recognition of a fact. When Kelsey and I moved to New York two years ago, our budget was set by the limitations of a doctoral stipend from CUNY and the salary of a pre-doctoral fellowship at the Federal Reserve. Rents in much of the city (particularly the easily accessible and historically white areas) are out of control which meant that we would either be moving into a historically minority area or moving to a neighborhood with immense commutes.

We chose the former.

We did our homework, though: Crown Heights topped our list because we figured that our incremental presence in a neighborhood with a relatively high rate of home ownership would have less impacts on rents and displacement than it would other places. We knew that new development was happening in Crown Heights, meaning again that our marginal increase of demand might be offset by increases in supply. I attended meetings of the Community Board 8’s Economic Development Committee, hoping to learn about and support the needs of local businesses in the area, and we’ve made conscious decisions to support Black Owned Businesses. We’ve given time and monthly money to SOS Brooklyn, a really great organization working to lessen gun violence in the neighborhood.

And yet.

We’re still gentrifiers. Our presence as a young, white, educated couple with a reasonably large disposable income sets us apart from the long-standing community. Any attempt to pretend otherwise or ignore the fact that our presence makes newer-comers feel more comfortable here is an exercise in misplaced self-exculpation. I can try to be a “good gentrifier”, but the impact of my residence on the neighborhood should always make me feel a little uncomfortable.

My role in my community was thrown into sharp relief last week when a new bar three blocks from my place gave a press release. Crown Heights has seen more than its share of bars and restaurants open up over the course of the past few years, most to little fanfare outside the community board’s liquor committee. I likely would have tried out Summerhill before the end of the year – a three block walk, big garage door windows, and reasonably good looking sandwiches are hard to resist.

Becca Brennan, owner of the new restaurant, effectively ensured that Summerhill would be roundly rejected by the community. In the press release Brennan pretended that holes left in the wall by the shelving units of the old occupants were actually bullet holes, left over from some gang shootout. Brennan said that she’d be selling 40 ounce bottles of rosé wine, served in paper bags. When Gothamist picked the story up, she offered apologies through the press that seemed to reveal her inability to understand why the community was upset.

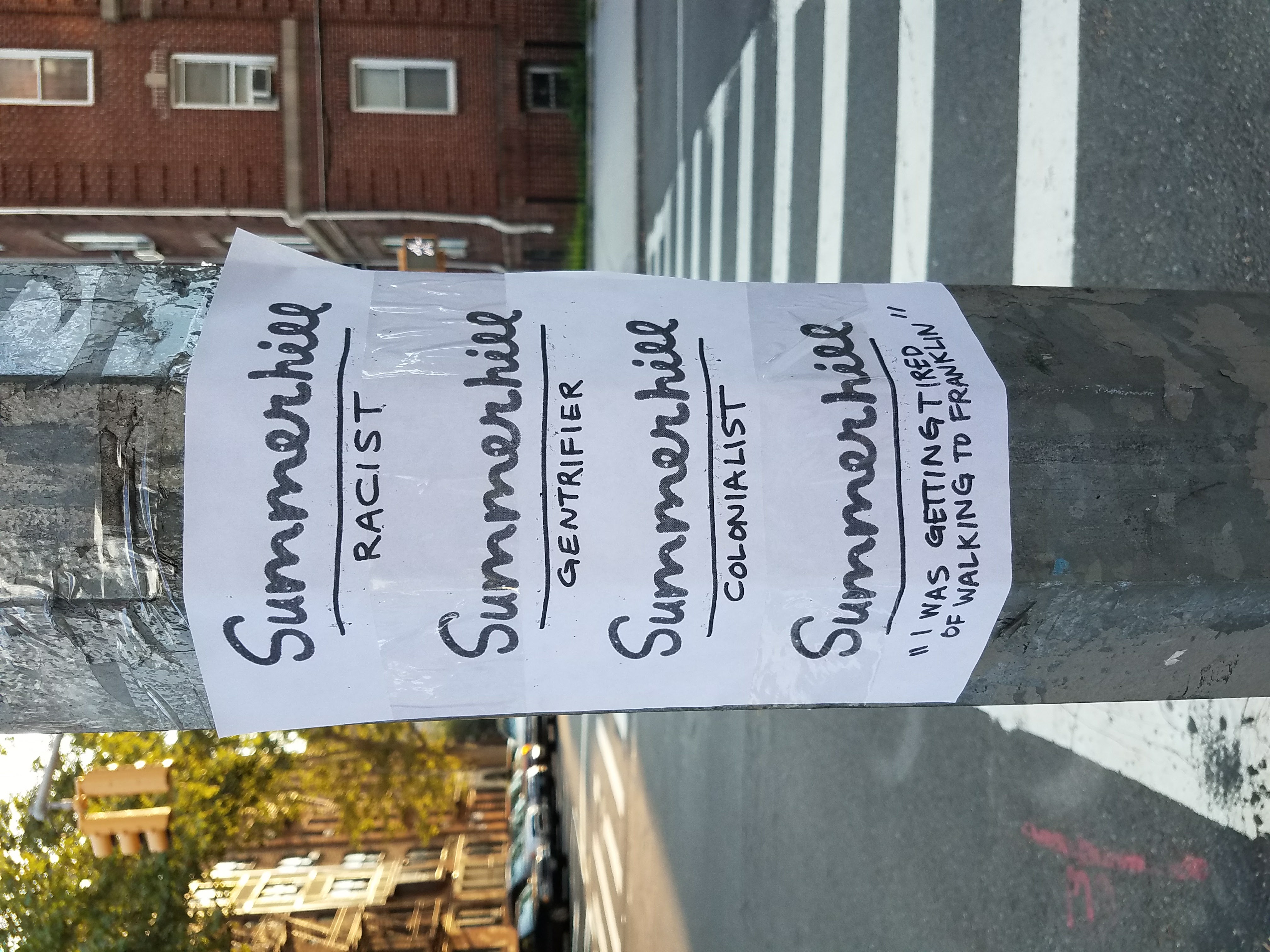

So, on Saturday afternoon, the community staged a protest outside the bar:

All told, about 100 people came to share their stories and to explain why they found the new restaurant so distasteful.

Gentrification is a much trickier issue than most people give it credit for. Last week I wrote about how gentrification can sometimes be a mixed bag, bringing new resources to a community along with displacement effects. That said, and while Summerhill is in fact employing neighborhood residents, the new restaurant is overwhelmingly an example of bad gentrification, no nuance required. Brennan, who has lived in the neighborhood for two years, is explicitly attempting to profit off the painful history of violence and disinvestment in Crown Heights. I’ve written before about how federal policy severely curtailed the flow of resources into Black communities like Crown Heights. The violence and relative poverty in areas like Crown Heights can be easily traced back through decades of lack of municipal investment, lack of mortgage and home improvement loan availability, a failed War on Drugs that treats addiction as a crime, and sustained racism in private sector hiring. These systemic failures led to an economic environment in which Black urban communities were essentially pushed out of the formal economy and into the black market, where the highest profits can often be found in the drug trade. (Sidenote: I’m making my way through Thomas Sugrue’s Origin of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit and it’s incredible and incredibly damning. There’ll likely be a post on it in the near future).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a market has grown up selling the culture that grew out of this still-present segregation. This lily-white guy remembers listening to Jay-Z (who grew up in the Marcy Projects just a couple miles from Summerhill) in the suburbs of Portland, Oregon. Becca Brennan, who hails from Toronto, is continuing the tradition of the capitalization of Black suffering. She knew that the holes in the walls weren’t from bullets, but she also knew that people love the evocation of danger, the vibe created from a glorification and Disney-fication of the very real and very present reality of gun violence. On Saturday, many longtime members of the communities recounted stories of loved ones who had been killed on the very street where Brennan has opened Summerhill. For them, it’s no vibe – it’s the dangerous, heartbreaking outcome of a system which has consistently denied them full membership in the economy of the city.

The reference to 40 ounce bottles served in paper bags attempts to profit off the same history. Malt liquor has a long history in Crown Heights and other Black communities in New York, the cheapest relief around from the systemic injustices suffered for generations. Brennan once again takes a symbol of the harmful results of systemic disinvestment and looks to profit off its cool, edgy associations with suburban white kids moving to Brooklyn – people like me.

The way I see it, as a student of urban history and current residential dynamics, my job is two-fold. First, it’s to shut the hell up. White people in power have spent too long in this city and others proposing new projects and new ideas and new programs to help minorities and low income folks, assuming that we know best. It hasn’t worked. We need to listen to the stories of folks who live in neighborhoods where rents are going up, where businesses are being pushed out, and where change is wrenching. Yes, we need to build more. No, we can’t sacrifice the good of the city because of local NIMBYs (but as Lisa Schweitzer wrote the other day, we’re out of our minds if we don’t distinguish between people who are anti-development because they don’t want a view blocked and those who think they’re going to lose their homes and communities). But we need to do some deep listening and some deep study of the policies and decisions that led to the current distribution of resources and people in the US’s cities today. We need to hear the stories of the people most impacted by our work.

My second job is to call out the bullshit of the people who look like me. Let’s face it – Summerhill doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Summerhill exists because I chose to move to Crown Heights two years ago. Summerhill exists because of the white people who want to live in a historically disenfranchised neighborhood, and want to have stories to tell – “Can you believe I’m drinking in a bar with bullet holes in the wall? Crazy!” Community is hard work. Letting yourself be uncomfortable with the role you play in a neighborhood is hard work. But it’s up to us – as one woman at the demonstration put it, people of color aren’t responsible for teaching newcomers the neighborhood’s history. Our neighborhoods don’t exist ahistorically, and we don’t exist as ahistorical actors within them, regardless of when we moved in. It’s up to us to call one another out, and to recognize that how we spend our money in our communities has major implications for our neighbors. If we care about justice, if we care about reversing the trends of disinvestment and disenfranchisement for communities of color in American cities, we need to do the hard work of understanding how our actions interact with the large systems that have caused things to be the way that they are now.

2 thoughts on “Summerhill: Selling Urban Failure”

Good honest read. Thank for at least trying to understand. Peace.

Despite my desire to further the integration of neighborhoods, I don’t see my move to an African American neighborhood as a net positive for that neighborhood. I can’t see the world of neighborhood redevelopment as a credible vehicle for helping all to integrate. The cost of development often requires the use of income-targeted government funding, usually LIHTC, to supplement any homeowner or rental developer to produce a desirable home, especially when the market is expanded to buyers/tenants with families.

Having spent several years the government representative in such deals, I still feel a sense of guilt that my work produced only a simulation of mixed-race and mixed-income neighborhoods.

We in Baltimore are still missing the strong development/government leadership to help guide us to live together, a situation we were once hopeful that HOPE VI developments would provide. People who can convince us of the advantages of living together are in short supply. Few towns or neighborhoods are able to expend the effort to live out their commitment to integrating people of multiple races, ages, family types and incomes.

Are people lurking out there to help us ave this kind of life? Are people interested in voluntarily joining in creating and living in such neighborhoods?