Failure to Serve: ADA Accessibility in NYC

It is no secret that the New York City transportation network is currently in dire straits. The public transit system in the city is groaning under the weight of a booming population and a history of financial neglect, and service has markedly deteriorated across a broad array of metrics. As city residents rightly voice their frustrations with the current state of service, however, the voices of a particularly vulnerable population are at risk of being drowned out. For those who live, work, or travel to New York City and have physical disabilities, the city has always been a difficult place to get around and it is getting worse. City agencies and the Metropolitan Transportation Agency (MTA) alike consistently fail the population with disabilities as they focus scarce resources on other challenges. The result of this disinvestment has been the further marginalization of an already-vulnerable population. According to 2015 census data 6.7% of New York City residents have an “ambulatory difficulty,” a proportion that is sure to grow as the population ages. Finding ways to better incorporate these people into the city is of paramount importance.

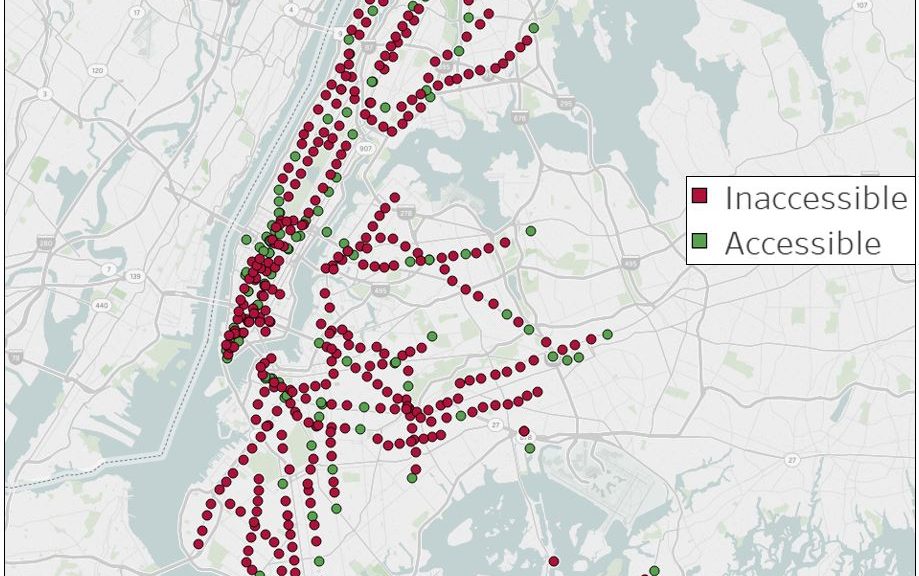

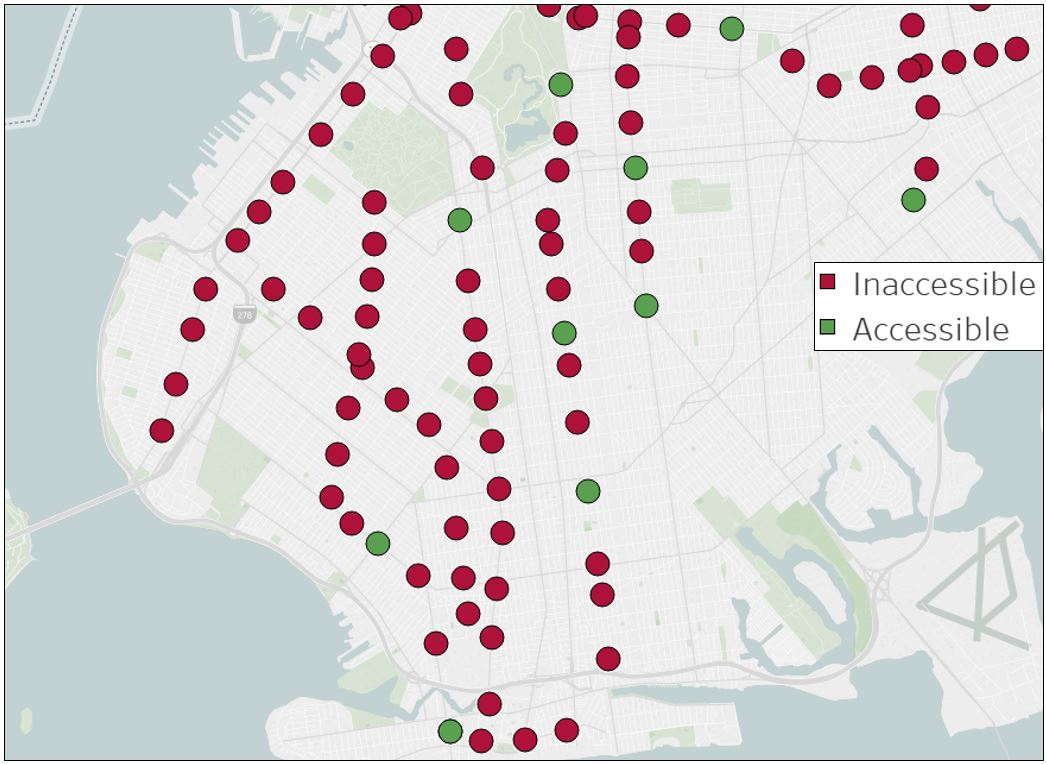

New York City Transit (NYCT), run by the MTA, is one of the great engineering feats of the United States. With nearly 400 kilometers of track and 472 stations, it averages more than five and a half million riders each weekday. Nevertheless, only a paltry 23% of NYCT stations have elevators. The remaining stations are entirely inaccessible to riders in wheelchairs and pose significant challenges to riders with other physical disabilities. This 23% figure, however, masks wide spatial inequalities in the distribution of ADA-accessible subway stations: while more than 38% of stations located below 110th Street in Manhattan have elevators, just 17% of stations elsewhere in the system are similarly equipped. In some areas, such as Brooklyn south of Prospect Park the lack of accessible stations is particularly acute.

The concentration of stations with elevators in the borough of Manhattan is clearly an attempt to focus capital expenditures in stations with large passenger volumes. It also, however, has another and more pernicious result: high income Manhattan neighborhoods receive much better elevator service than lower income neighborhoods in the outer boroughs. The presence of wealthy neighborhoods near areas with concentrated jobs, services, and amenities is the normal outcome of a city in which the spatial mobility of wealth is largely unchecked. The placement of elevators in high-traffic stations is explicitly the placement of elevators in areas dominated by the wealthy. Manhattan’s 34% share of ADA accessible stations far outweighs its 18% share of New York City residents with an ambulatory disability. Moreover, the unemployment rate for residents with ambulatory difficulty in the city is double that of the general population. The overconcentration of elevators in wealthier Manhattan neighborhoods where relatively fewer residents with disabilities can afford to live further compounds these spatial inequalities.

The distribution of elevators does not mark the full extent of the neglectful service provided by NYCT to riders with disabilities. An audit earlier this year from New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office detailed just how woefully NYCT is failing to meet their stated goal of 96.5% availability for elevators throughout the subway system. The audit revealed that a third of scheduled maintenance was performed either late or not at all, and concluded that NYCT “cannot ensure that its 407 elevators and escalators are presently, and will continue to be, in good operating condition.” Thanks to this lack of maintenance it should come as no surprise that the subway averages 25 outages per day (that number comes from a great piece Transit Center did earlier this year looking at all these same issues). Even after a person with a disability has organized their trip in such a way to ensure that both the start and end stations are equipped with elevators, there is no guarantee that they will in fact be able to use either station. The need to redesign a route upon arriving at a station and finding it inaccessible imposes large time costs on riders. Furthermore, NYCT is notoriously bad at publicizing elevator outages, limiting riders’ ability to plan ahead.

Despite the City Comptroller’s condemnation of NYCT’s ability to maintain accessibility in the few stations where they do have elevators, the city itself is responsible for further undermining the mobility of residents with physical disabilities. The expansion of transportation network companies (TNCs) in New York City has systematically undermined the mobility of residents with disabilities. In 2013 the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) settled a suit brought against them by four disability rights organizations. As part of this settlement the city agreed to make 50% of the taxi fleet wheelchair accessible by the year 2020. This is a costly investment, but it was necessary. The lack of accessible NYCT stations in large swaths of the city effectively bars the population with disabilities from the subway. In a city where most households do not own a car and most workers commute by public transit the city has an ethical obligation to provide alternative forms of transportation. Uber, Lyft, and other TNCs, however, have no contractual obligation to provide any wheelchair accessible vehicles. In their haste to negotiate a deal with the TNCs the city allowed these companies to refuse to serve the city residents who are most in need of alternatives to the mass transit system. The city’s promise to make half the taxi fleet wheelchair accessible looks emptier and emptier as TNCs continue to eviscerate the taxi industry. By not requiring these private companies to provide services to the New Yorkers who live in the outer boroughs and are excluded from mass transit, the city is failing even at providing a stopgap measure to combat the neglect of NYCT.

State and city agencies in the New York region are woefully failing the community of people with disabilities. Even when NYCT does provide elevators in stations, these stations are concentrated in parts of the city where few but high income residents can live and service is unreliable. Higher unemployment levels for this community pushes them to the far-flung areas where elevator service is entirely inadequate. Once there, the city abandons them to private mobility companies who have determined that the wheelchair-bound are too expensive to court as customers. Under the best of conditions these residents would face myriad challenges moving around their city, and dismissive attitudes from city and state agencies make it dramatically worse.

4 thoughts on “Failure to Serve: ADA Accessibility in NYC”

the Capital Costs of upgrading a 19th Century public transportation system are impossible to overcome in all but the newest stations. Having worked on this issue in NYC for 30 years, we never catch up. In the interim, alternatives like Uber and Lyfft and even Taxis have come along as alternatives. Those methods or voucher type systems are going to be the only answers in our lifetime, especially in light of domination of government by Republicans that have calculated costs and decided that this agenda is also like the other 19th century ideas that they are determined not to fund – that the money doesn’t buy enough votes..

You’re definitely right – it’s incredibly expensive. But even where we could do it we’re choosing not to. In Brooklyn, for instance, lots of stations have been entirely shut down for renovations for months on end – without any intent to put in elevators. The elevators are expensive, but the marginal cost relative to what’s being pumped into them now when they’re already out of service would have argued in favor of their installation.

More broadly, you won’t be surprised to have my full-throated agreement that conservative strangulation of funding for capital projects, especially at the local level, is one of the most problematic and damaging political trends of our time.

Obviously, infrastructure maintenance has been woefully underfunded for too long, and details like accessibility are easily dismissed. But if the government cannot manage to satisfy their own regulations, is it fair to dump the problem onto the business community?

Hey Ken! That’s a thorny question – the Americans with Disabilities Act does require companies like airlines and taxis to provide some level of accessibility, which the city has failed to enforce. That said, obviously pointing to existing laws doesn’t answer the question of whether the government should be doing that. If the city were doing better for this community, they’d be on much stronger footing to push the for-hire companies to provide better service. I think there’s actually an enormous amount of room for compromise and innovative thinking on the issue – chiefly, the city ought to be providing financial incentives / contracting with these companies to provide ADA service. Doing so would both be cheaper than building elevators and would make the provision of service financially viable for the private companies.