John Kelly, Buchanan v. Warley, and the Birth of a Lie

I’ve got a few things banging around in my head this week. They’re all connected in some sort of way, but I’m trying to figure how exactly I think they relate. So I’m using this space to process “out-loud”, and I hope you’ll jump in in the comments to give me your thoughts so we can work through all of this together.

First of all, last Sunday (November 5th) marked the 100 year anniversary of the Supreme Court decision in Buchanan v. Warley. A brief history: William Warley, a black man, made an offer on a property in Louisville, Kentucky, being sold by a white man named Charles Buchanan. Buchanan accepted Warley’s offer, but Warley then reneged. Warley pointed to Louisville’s zoning code that prohibited a black person from living in a predominantly white neighborhood. The case made its way up to the Supreme Court, and the Court ruled unanimously that Louisville’s zoning laws explicitly preventing people from living in certain neighborhoods because of the color of their skin unconstitutional.

The ruling was a big deal, especially considering the fact that Chief Justice Edward D. White was an honest-to-god ex-Confederate soldier. Of course, we know how the rest of the story goes: cities found other ways to ensure that black families were unable to move into white neighborhoods. Although it wasn’t allowed into the zoning code local, state, and federal agencies found ways to enforce and reinforce residential segregation. A decade and a half after Buchanan v. Warley, FDR’s Federal Housing Administration introduced red-lining, a practice that echoes all the way to today. Even as many Americans today decry the legacy of apartheid in South Africa, we forget that a developer in Detroit was denied federal funds for new building until he literally built a wall between his land and the black community neighboring it. Upon demonstrating his commitment to keeping black families out, he was granted funding:

As I wrote a few weeks ago, the United States is still a racially segregated country. Despite the ruling in Buchanan v. Warley, the 1968 Fair Housing Act, and other half-hearted attempts to undo the historical legacy of segregation, the facts remain. Today, rather than explicitly zone areas using race, we use income: by mandating minimum plot sizes in suburbs, municipalities can ensure that poor families can’t move in. Thanks to the nation’s entire history, prohibiting low-wealth families from moving into certain towns does a pretty damn good job of making it difficult for brown and black families to move in. You’ll forgive me for not being among the people celebrating the anniversary of a Supreme Court ruling that we’re still finding ways to circumvent a full hundred years later.

The other thing I’ve got running through my head, in parallel and conjunction with the centennial of Buchanan v. Warley, are the asinine comments made by John Kelly last week. In case you somehow missed them, he argues in a single breath that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man and that the Civil War was caused by a lack of an ability to compromise:

I’ll let Ta-Nehisi Coates do most of the takedown of this argument here (be sure to read the whole thread):

https://twitter.com/tanehisicoates/status/925289478943633408

But I want to point out a few things. First of all, the idea of compromise is demonstrably bull-shit. The North continuously compromised on the issue of whether or not the ownership of other human beings was allowable. It seems that Kelly was home sick with a tummy ache on the day in elementary school when we learned about how slaves would be counted in the constitution for representation based on population. The Three-Fifths Compromise has “compromise” in the goddamn name. The Missouri Compromise, passed in 1820, allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a slave-holding state. The Fugitive Slave Law, passed in 1850, allowed Southerners to send body snatchers to recapture runaway slaves from areas where they were legally free. The North consistently tried to compromise with the South. The North stood firm on one thing, and one thing only: not that slavery should be abolished, but simply that it shouldn’t spread in such a way that free whites would have to compete in the labor market with infinitely-cheaper slave labor. Let’s not forget that the North didn’t start the war: it was the Southern states, dissatisfied with the North’s concessions, that fired first. Their founding documents point to centrality of slavery in their decision to secede.

But let’s also take one giant step backward: when Kelly says that a “lack of compromise” sadly led to war, what exactly is he saying? There’s only one reading of that statement: the North should have been more accepting of the South’s desire to enslave human beings. He doesn’t comment that the Civil War was caused by the North’s unwillingness to help the South transition away from an economy based on slavery. The not-so-subtext is that the North should have found it in their hearts to let the South continue to own humans. The problem with the end of slavery, says Kelly, is that it came too quickly. And let’s be clear: as problematic as Kelly and the Trump administration are, they aren’t the whole problem. They wouldn’t be saying this stuff if Americans didn’t believe it. People would still think this stuff even if HRC were president right now.

The other point Kelly makes is equally stupid: the idea that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man. By choosing to support secession, Lee says that what he wants (IE, ownership of human beings) is more important to him than fealty to the Constitution and the country as a whole. It’s hard to imagine anyone in the Trump administration calling anyone leading an armed insurrection against their leadership honorable. And yet somehow the White House Chief of Staff referring to a traitor who raised arms against the country as honorable doesn’t boggle the national mind. It’s as if Angela Merkel were to refer to Hitler as someone she respected: “Well, yes, he killed millions of people, but he really cared about Germany! And boy did he stick to his principles! Even if you disagree with him (and I do, pinky swear), you have to respect his honor.”

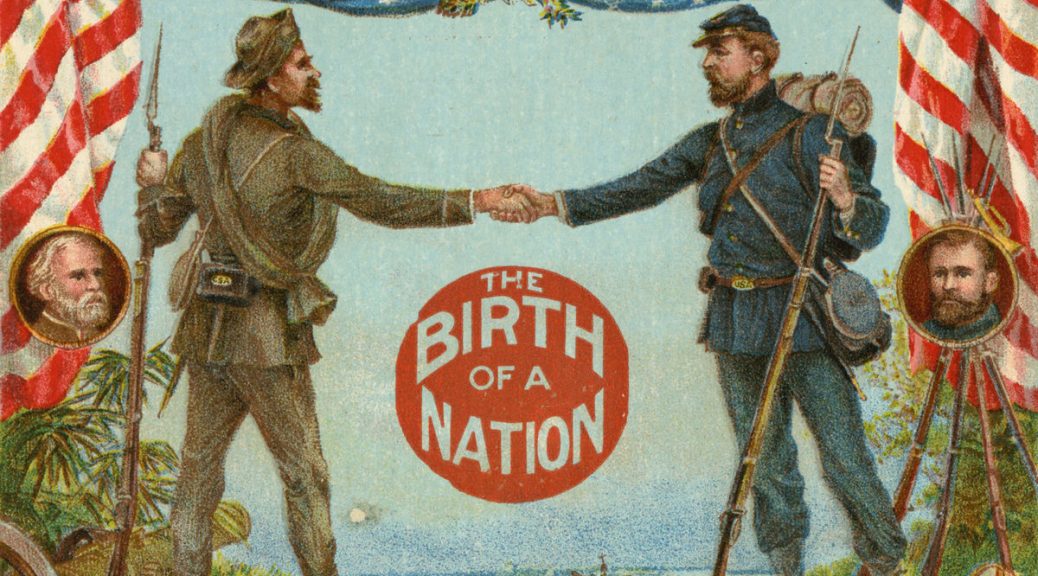

I’m also reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ We Were Eight Years in Power (three cheers for friends who know exactly what we want for our birthdays). Re-reading “Why Do So Few Blacks Study the Civil War?” was eerie: Coates addressed pretty much exactly what Kelly spews back in 2012. Following the Civil War, the North was so intent on reunification that they let the South spin their narrative however they wanted. They let them erect statues, and somehow the flag of a traitorous army that put slavery above nation continues to be a symbol that evokes pride for some in this country. Black people don’t study the Civil War, Coates argues, because the false narrative shifted the focus of the war away from emancipation and the idea of whether black people deserved to be owned to questions of states rights.

We owned people. Southern states thought it better to form a new country to give that right up. The North considered an end to fighting and reunification more important than ensuring that the South’s beliefs about black people was effectively removed from public policy. What flourished was a story not of traitors defeated but brothers reunited. The North and the South both continued to treat black people as second class citizens. We continued to make policy based on that belief. We still make policy based on that, in our residential zoning laws, in our criminal justice system, in our education system. Some Southerners still take pride in men who sent their sons off to be killed in battle rather than give up the right to own other people. And here’s the kicker: when we still haven’t addressed the fact that half the country was willing to fight and die for that right, when we talk about inability to compromise and honorable men, we minimize the historical legacy of that system. When we say that the Civil War wasn’t really about slavery, we tacitly say that mistreatment of black people in this country wasn’t really a problem. And if we say it wasn’t really a problem when people were enslaved, how can we say that wealth gaps and residential segregation and mass incarceration are a problem?

So sure, celebrate the centennial of Buchanan v. Warley. I won’t join you. Dubois said that the ruling began the breaking of the “backbone of segregation,” but he was wrong. In 2017, when the White House Chief of Staff regrets that the North wasn’t even more compromising on the issue of human ownership, we shouldn’t be surprised to look around and see that we managed to accomplish, using state power, exactly what the Supreme Court ruled 100 years ago was antithetical to the Constitution.

4 thoughts on “John Kelly, Buchanan v. Warley, and the Birth of a Lie”

1.Retired 2.military 3.bureaucrat are the three strikes on Kelly’s resume. His opinions, as typical of the Trump-team, cannot be taken seriously. Let him return to his duties as dustpan-minder and duct tape enforcer and shut up about issues of any kind other than entry level maintenance. Let us concentrate our efforts on removing power from his boss.

Agreed – but I think that an over-focus on giving Trump the boot runs the risk of ignoring all the underlying things that gave rise to him. In that sense, I think of Kelly’s comments more of a symptom than as a cause of problems.

Last month Coates was on Ezra Klien’s podcast (link – go listen!). Klien asked him how his analysis would have been different had Clinton won, and he says it wouldn’t have been. I’ve been thinking about that a lot. There’s a sense in which Trump’s presidency is forcing us to engage with things that have been under the surface for a long, long time that would have been there either way, whether or not the sheen of a Clinton presidency would have allowed us to ignore them. I don’t know. I’m in a very cynical place these days. For all the horrors being done by the Trump administration, this season doesn’t find me hopeful that removing him would necessarily fix very much at all.

1. Most lifetime military personnel are probably not equipped to speak on social issues.

2. Many racial practices are just an excuse to financially take advantage of a large group of people.

3. Anyone who minimizes the effects of racism isn’t the target of it.

You’re definitely right here, and it’s something I keep chewing on. On the one hand, I’m frustrated with the “gotcha-ism” of harping on Kelly’s comments, because he isn’t someone who is, as you said it, “equipped” to speak on the issues. It feels too much like scoring cheap political points. On the other hand, someone more equipped to speak might be more able to hide their ulterior motives, so Kelly may be giving us a “truer” look into how he and others really think precisely because he doesn’t know the polished way to put it. At the end of the day, though, Kelly isn’t so much the problem. The bigger problem is that some people still think this way, and that would be true whether or not Trump and Kelly were in power.