Walking While Black

Since the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012, it seems we’ve seen an endless number of black men and women killed in the United States. In many cases, the murder of these citizens was committed by the government by means of the police departments. And many of these killings by the police started in the same place: the overly aggressive enforcement of traffic laws.

On the night he was murdered, Philando Castile was pulled over for a cracked tail light. In the previous 13 years, he had been pulled over 49 times for such infractions as having an unlit license plate and turning into a parking lot without signalling.

Terence Crutcher was having car troubles on the night he was murdered. He was standing next to his car when the police pulled up. They shot and killed him.

Sandra Bland was 28 when she was found dead in police custody. Her crime, which effectively resulted in the death penalty? She failed to signal before changing lanes.

Some will wave their hands and say that, surely, the victims did something to strike fear into the hearts of the police. That they were responsible for escalating the situation. But the fact is, the way these individuals acted doesn’t really matter at all. The more often someone interacts with the police, the more likely they are to have a violent interaction. The most surprising thing about Philando Castile may well be the fact that he had 49 interactions with police before things turned horribly ugly.

According the the Justice Department’s own data, black drivers are consistently more likely than white or Latino drivers to be pulled over by the police. Just as it’s impossible to know which of Mark McGwire’s homers were attributable to skill and which to steroids, it’s impossible to know which police incidents are attributable to racial bias – but being unable to indisputably identify individual incidents doesn’t obscure the underlying patterns.

The same patterns are present for black citizens walking in their neighborhoods and cities. Yesterday, Vox and Propublica did a piece on “Walking While Black”, centered in Jacksonville, Florida. The whole thing is worth reading, but since you all pretty much never click through to articles I tell you to read, at least watch the video:

I think there are really two things going on at once here. The first is just plain ol’ racism. The prevalence of racial bias in who gets pulled over for traffic stops is so widely documented that it has it’s own Wikipedia page. Here’s what the references for that page look like:

Yeah. There’s a lot of evidence to support it. But if you think the police don’t pull over black and brown drivers more than white drivers, you probably stopped reading my blog a long time ago*. And the ProPublica piece gets into that: they quote black teenagers who say that the cops stop them just to make sure that they didn’t have guns or drugs on them as they’re out walking. Or stopped them just for wearing a hoody.

What I’m more interested in this week is how the transportation infrastructure in places like Jacksonville can reinforce and exacerbate racial disparities. As the piece points out again and again, Jacksonville is a city built for the automobile. Like many, many cities in the United States, driving is the primary mode of transportation: in 2015, 81% of workers in Jacksonville and 76% of all Americans drove to work without carpooling, according to Census Bureau data. When such a large portion of the population drives itself to work (and less than 2% use public transportation), it’s unsurprising that pedestrian and public transportation infrastructure is severely lacking. These under-performing links then force people to jaywalk and commit other technically illegal actions. But you tell me: faced with this, would you retrace your steps to the nearest intersection, or try to just cross the street?

We both know the answer.

Of course, the population that is adversely impacted by crappy pedestrian infrastructure and then ticketed for finding ways around it isn’t randomly selected from the population at large. In 2015 in Jacksonville, for instance, the median worker who drove herself to work earned just over $31,800. The comparable number for someone who takes public transportation? Just $16,031. Not only are the poorest Jaxons given lame bus stops and dangerous sidewalks. They’re also more likely than any other population to be fined because of it.

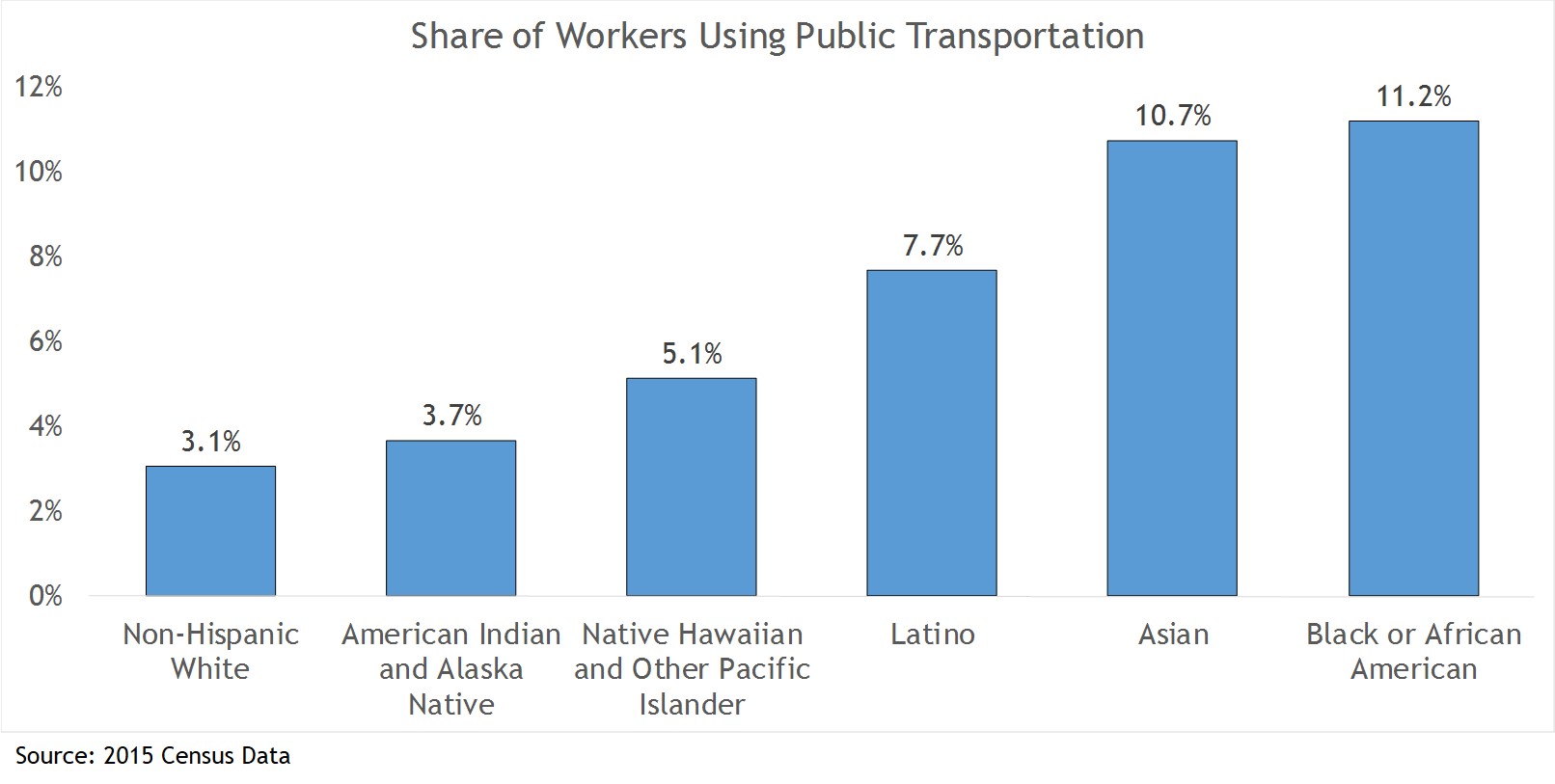

However, these numbers obscure the distribution across racial groups, as so many aggregate level statistics do. When we break down the national numbers, we see that minority workers are far more likely to take public transportation to and from work than white workers:

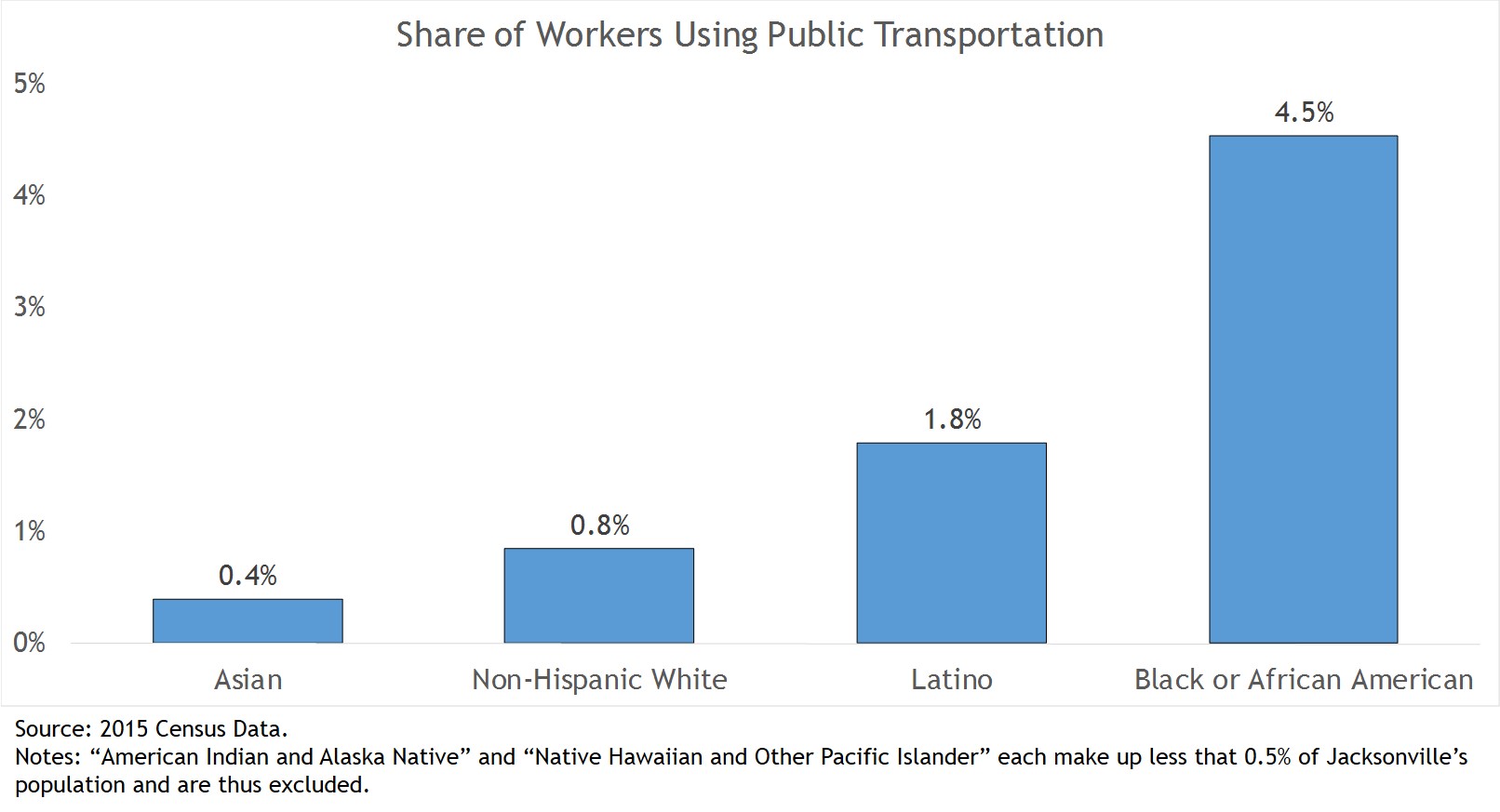

While many fewer people of all races take public transportation in Jacksonville, black workers are more than 5 times more likely to use public transportation than white workers in the Florida city:

In the piece, ProPublica quotes the sheriff’s department’s second-in-command, Patrick Ivey, as saying “Any racial discrepancies could only be explained by the fact that blacks were simply violating the statutes more often than others in Jacksonville.” Considering the fact that black residents make up 29% of the population and receive 55% of pedestrian tickets, that’s a little tough to swallow. I’m not inclined to buy it.

But even if we do accept Ivey at face value, that still doesn’t excuse the police department or the city. The infrastructure in Jacksonville encourages all walkers equally to violate technicalities in the law. But because black residents are so much more likely to take the buses, they are more likely to face a system that encourages them to break the law. Even when applied in an unbiased way, laws that penalize behavior more likely to be observed in certain populations because of other structural issues can themselves be racist. There are strong echoes here of sentencing disparities between crack and powder cocaine: even if these laws are applied evenhandedly, when the form of the drug associated with black communities carries much stronger penalties than the same drug in a different form, the law is still implicated in deeply racist outcomes. So-called unbiased laws are not immune from reflecting and amplifying underlying iniquities.

Worse still, when officers have the freedom to selectively enforce laws, abuse can happen in an instant. It’s hard to imagine a law more selectively enforced than jaywalking. The design of our streets makes it all but inevitable – but because the law is on the books, the routine act of crossing the street gives an officer of the state a reasonable cause to stop just about anyone they want, for whatever underlying reason that they want.

Design doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Transportation systems don’t happen in a vacuum. That’s neither a good nor a bad thing, but we get into big trouble when we pretend that they are. Whether or not the Jacksonville police department is actively engaging in blatantly racist activity, they have some soul searching to do. When your policies result in a black resident being more than twice as likely to get a ticket for something than a white resident, you’ve got two options. You can explain it away by saying that black folks are somehow more likely to break the law, a spurious and deeply racist response on its own. Or you can do the hard work to try to understand why black community members find themselves in positions where they are more likely to break the law, and address those issues. One of them is much harder than the other. But it’s absolutely necessary.

* To be clear, I don’t think that police officers are or are not any more racist than the rest of us. It’s just that the rest of us don’t have to make decisions about who to pull over, who to arrest, and who to use the power of the state against. I have no reason to believe that my actions if I were a police officer wouldn’t be driven by racial bias; I’m just lucky to not be in that position.