Spotlight Boston

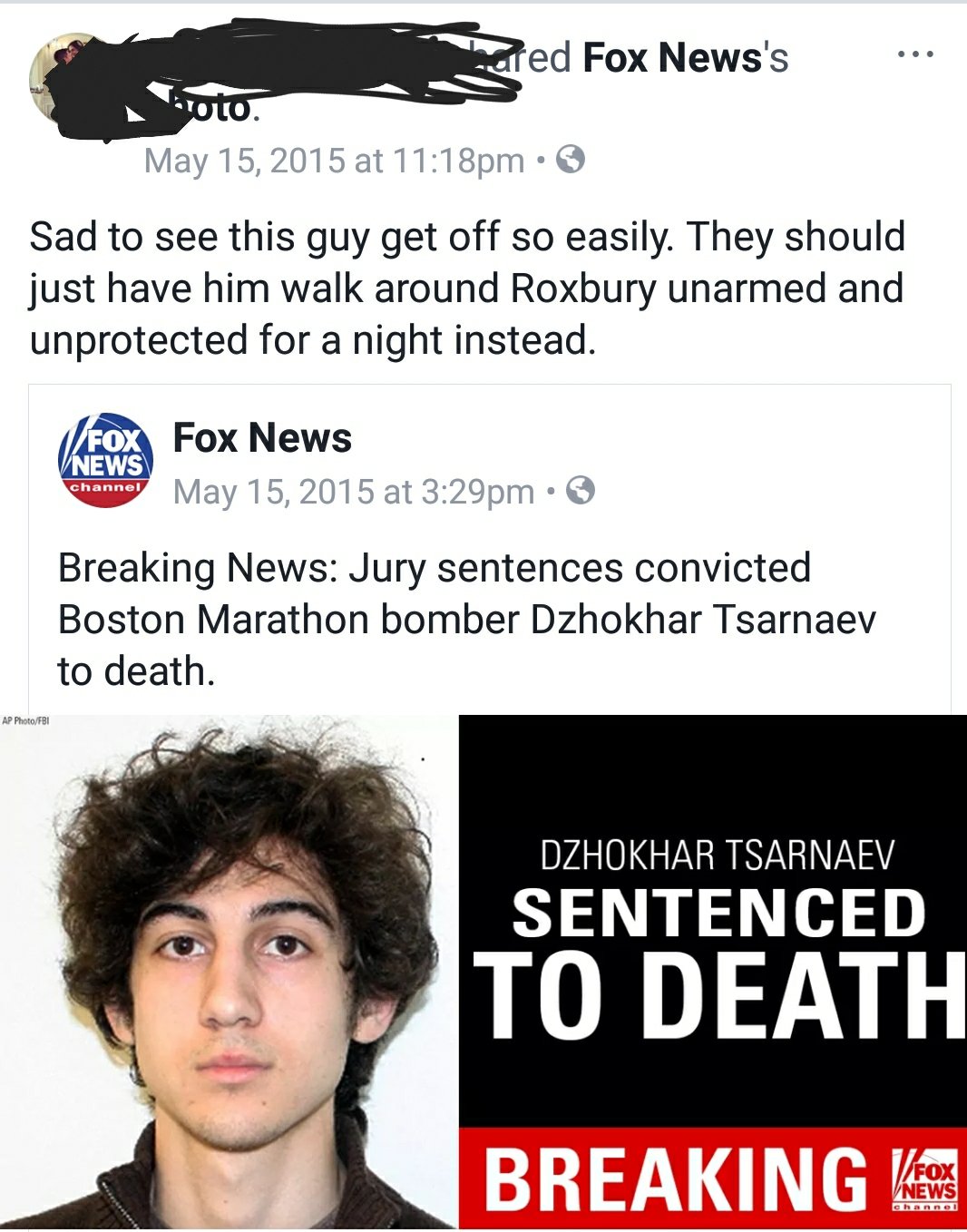

Once upon a time, I had a very very bad roommate. I’ll never forget the night we found out Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (one of the brothers responsible for the Boston Marathon bombing) would be getting the death penalty. It was an odd moment in Boston and it raised a lot of feelings. This roommate, however, was pissed.  She was from Boston, and it’s a comment that has stuck with me. The comment encapsulated so many of my weird and uncomfortable feelings in such a direct way. First is the blatant racism in it: Roxbury is a predominantly black neighborhood (56.9%, while the city itself is 22.8% black) and, for lots of Bostonians, is synonymous with crime and danger. My roommate’s operating assumption was that Tsarnaev would be killed(or tortured?) if left in Roxbury because people there are so violent. A disgusting statement. The comment, however, threw something else into relief that had consistently bothered me surrounding all the reporting that went into the Boston Strong / Boston Marathon Bombing narrative for the two years I was in the city after the bombing. In both the narrative Bostonians tell themselves and the image of the city that’s projected to the world, Boston is a monolith. The Boston Marathon Bombings, the narrative goes, attacked all of Boston. Good Will Hunting and The Departed and Manchester by the Sea capture the essence of Boston in deep and insightful ways. But that’s not the case, or at least not my experience of Boston. As galling to me as the “Roxbury is full of killers” narrative was the narrative that the bombing was as big of a deal to low income and minority communities as it was to the college students and professionals for whom Marathon Monday is a day of celebration and a paid holiday. To be clear, I don’t mean to minimize the impact of the bombing at all. I’ll never forget standing on the route, piecing together which friends were likely to be near the finish line when the devices detonated and waiting to hear from them. Three people died, and that’s a big deal. I also don’t mean to say that communities in Dorchester and Roxbury and Mattapan weren’t impacted – of course they were. But my roommate’s comment reflected another troubling thing about how white Bostonians tend to look at the city – myself included. We think that the narrative of the white/educated/professional world is the narrative of the entire city. Everyone in Boston is connected to the marathon. Everyone in Boston is connected to St. Patrick’s Day and Irish heritage. Everyone in Boston claims the Kennedys as their own. When you’re on the inside (when you’re a Catholic college student who interns in John Kerry’s office and is of Irish decent), it’s an exhilarating narrative. It feels like the city was cast in your image and was built as a playground for people just like you. And I mean that very seriously. Boston is one of the great loves of my life because it feels so much like home. From the food to the bars to the music, the city is eerily and wonderfully tuned into what I like. But a strong narrative – We are Boston and Boston is this – creates outsiders in direct proportion to the extent it creates insiders. A monolithic identity necessarily casts those that don’t conform to that narrative into the shadows. A series of articles from the Spotlight team at the Boston Globe (yes, that Spotlight team) digs into what Boston means for black residents who don’t fit that dominant narrative and are subsequently left out of the city’s conception of itself. The stories are uncomfortable and challenging and damning, and they cry out for honest engagement. I encourage you to read the whole series, particularly if you live in or love Boston like I do. I’m going to write more about the series over the next couple days, and was planning on waiting to publish this draft until I wrote more. But I decided to let the blog move through the response process with me. I’m starting by lamenting. I’m sitting with the recognition that what makes me love Boston is what makes it inhospitable for others. I’m sitting with the sadness and, before analyzing it more “quantitatively” or “rationally” or “objectively”, I’m letting myself feel it. Once its in my bones we can look at what it means Economically and Socially and everything else, but since policy commentary that doesn’t start from the heart doesn’t really mean much, we’ll leave it here for today.

She was from Boston, and it’s a comment that has stuck with me. The comment encapsulated so many of my weird and uncomfortable feelings in such a direct way. First is the blatant racism in it: Roxbury is a predominantly black neighborhood (56.9%, while the city itself is 22.8% black) and, for lots of Bostonians, is synonymous with crime and danger. My roommate’s operating assumption was that Tsarnaev would be killed(or tortured?) if left in Roxbury because people there are so violent. A disgusting statement. The comment, however, threw something else into relief that had consistently bothered me surrounding all the reporting that went into the Boston Strong / Boston Marathon Bombing narrative for the two years I was in the city after the bombing. In both the narrative Bostonians tell themselves and the image of the city that’s projected to the world, Boston is a monolith. The Boston Marathon Bombings, the narrative goes, attacked all of Boston. Good Will Hunting and The Departed and Manchester by the Sea capture the essence of Boston in deep and insightful ways. But that’s not the case, or at least not my experience of Boston. As galling to me as the “Roxbury is full of killers” narrative was the narrative that the bombing was as big of a deal to low income and minority communities as it was to the college students and professionals for whom Marathon Monday is a day of celebration and a paid holiday. To be clear, I don’t mean to minimize the impact of the bombing at all. I’ll never forget standing on the route, piecing together which friends were likely to be near the finish line when the devices detonated and waiting to hear from them. Three people died, and that’s a big deal. I also don’t mean to say that communities in Dorchester and Roxbury and Mattapan weren’t impacted – of course they were. But my roommate’s comment reflected another troubling thing about how white Bostonians tend to look at the city – myself included. We think that the narrative of the white/educated/professional world is the narrative of the entire city. Everyone in Boston is connected to the marathon. Everyone in Boston is connected to St. Patrick’s Day and Irish heritage. Everyone in Boston claims the Kennedys as their own. When you’re on the inside (when you’re a Catholic college student who interns in John Kerry’s office and is of Irish decent), it’s an exhilarating narrative. It feels like the city was cast in your image and was built as a playground for people just like you. And I mean that very seriously. Boston is one of the great loves of my life because it feels so much like home. From the food to the bars to the music, the city is eerily and wonderfully tuned into what I like. But a strong narrative – We are Boston and Boston is this – creates outsiders in direct proportion to the extent it creates insiders. A monolithic identity necessarily casts those that don’t conform to that narrative into the shadows. A series of articles from the Spotlight team at the Boston Globe (yes, that Spotlight team) digs into what Boston means for black residents who don’t fit that dominant narrative and are subsequently left out of the city’s conception of itself. The stories are uncomfortable and challenging and damning, and they cry out for honest engagement. I encourage you to read the whole series, particularly if you live in or love Boston like I do. I’m going to write more about the series over the next couple days, and was planning on waiting to publish this draft until I wrote more. But I decided to let the blog move through the response process with me. I’m starting by lamenting. I’m sitting with the recognition that what makes me love Boston is what makes it inhospitable for others. I’m sitting with the sadness and, before analyzing it more “quantitatively” or “rationally” or “objectively”, I’m letting myself feel it. Once its in my bones we can look at what it means Economically and Socially and everything else, but since policy commentary that doesn’t start from the heart doesn’t really mean much, we’ll leave it here for today.