What I Learned This Year

Any fair consideration of the depth and width of enslavement tempts insanity. First conjure the crime – the generational destruction of human bodies – and all of its related offences – domestic terrorism, poll taxes, mass incarceration. But then try to imagine being an individual born among the remnants of that crime, among the wronged, among the plundered, and feeling the gravity of that crime all around and seeing it in the sideways glances of the perpetrators of that crime and overhearing it in their whispers and watching these people, at best, denying their power to address the crime and, at worst, denying that any crime had occurred at all, even as their entire lives revolve around the fact of a robbery so large that it is written in our very names. This is not a thought experiment. America is literally unimaginable without plundered labor shackled to plundered land, without the organizing principle of whiteness as citizenship, without the culture crafted by the plundered, and without that culture itself being plundered.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, We Should Have Seen Trump Coming

Thanks, guys.

I started writing this blog in February for a number of different reasons. I wanted to try writing to see if I liked it (I do). I wanted to bring friends and family into the big conversations I’m engaging with (thanks, Dad, for consistently disagreeing with me and helping me to sharpen my thinking). I wanted, generally, to force myself to engage critically and formally with what I’m reading and thinking (spoiler alert: I’m a nerd, and I read a lot). But the spark that set it all off was the confluence of books and pieces I read last winter that made me realize I needed to share what I was discovering. That kind of came to fruition a couple months later in the two pieces I wrote on red-lining and the mortgage interest deduction, but I never really talked about my relationship with the pieces that started it, and how they catalyzed this blog. The pieces were, roughly*, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Case for Reparations, Beryl Satter’s Family Properties, and Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns.

Last fall, I re-read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2014 piece in the Atlantic titled The Case for Reparations. I’ve told you before that you should read it. Maybe you have, and maybe you haven’t. But I’ll say it again – go read it. In a lot of ways it is the foundational text of this blog and the way that I think about justice in cities. As lots of you know, I’ve been banging around the idea of how urban areas and social justice are related for years now. My re-reading of the Coates piece was no doubt serendipitous in its timing, but it served as the shock that made all the rest of my thinking start to fall into place. If you’re nervous about reading something with “reparations” in the name, that’s a dumb reason to stay away. In the piece, Coates lays out the legacy of black families being locked out of the great wealth producer of the twentieth century: homeownership. During the twentieth century the United States used federal policy to encourage families to grow their wealth by investing their savings in their homes. At the same, government policy and social structures effectively barred African American’s from access to this wealth-building mechanism. The legacy is still with us: as I wrote last month, even today the median white family in the United States has $171,000 in wealth, most of which is tied up in home equity. The median black family, on the other hand, has just $17,000. This gap actually widened by some 20% following the housing crisis, because black families were systematically targeted for shitty loans. When people talk about the subprime mortgages, and the balloon payments, and the tricks the lenders used to get people into bad mortgages, these practices weren’t color-blind. Minority communities wore targets on their backs. Don’t ever forget that Wells Fargo talked internally about issuing “ghetto loans for mud people.”

In the piece, Coates spends a lot of time with Beryl Satter’s Family Properties, an incredible look at how these forces that locked black families out of wealth creation worked locally in Chicago in the mid-twentieth century. She details the human side of the story. She talks with families who were forced to work multiple jobs to pay for homes for which they couldn’t get mortgages, and about the bastards who recognized the immense profits that could be made in a bifurcated market. She talks about the efforts to fight back, and to prove the unconstitutionality of the housing covenant system. She explains how contract buying worked to make sure that black families would never actually own homes they were paying rent on but not building equity in. Basically, she puts human faces to all the ways in which black families were locked out of the twentieth century’s main push for wealth accrual.

Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns helped to put all of this in its historical context. She tells the story of black families leaving Southern states for Northern and Western cities in an attempt to flee Jim Crow. As these families moved to new cities, they were often used by companies as strikebreakers, often having their passage paid for just that reason. Wilkerson gives perhaps the most succinct summary of what this meant for black families in the receiving cities as the population boomed in neighborhoods whose borders were rigidly enforced:

The story played out in virtually every northern city- migrants sealed off in overcrowded colonies that would become the foundation for ghettos that would persist into the next century. These were the original colored quarters- the abandoned and identifiable no-man’s lands that came into being when the least-paid people were forced to pay the highest rents for the most dilapidated housing owned by absentee landlords trying to wring the most money out of a place nobody cared about.

Together, these historical pieces pointed to a narrative that explains the last fifty years in race relations. From the start of Nixon’s War on Drugs, Regan’s utter evisceration of funding for urban areas, Bush 41’s attack ad on Willie Horton, the Welfare Reform Act and to Donald Trump’s repeated references to Chicago and inner city crime – our policies systematically and intentionally forced black families into poverty and restricted them to certain physical places in our cities. After doing it for long enough, all us comfy white people forgot about how it started. Charles Murray led us to believe that inner city black families were there because of moral deficiencies, and we conveniently ignored the fact that when you use the power of the state to do such incredible violence against a community, that community might get sick. We forgot that our suburbs were nice because we locked the poor in the cities we left behind.

I’ll come clean. I’ve beat the drum on the ills created by homeownership over the course of this year, and I’ve used plenty of arguments to point out why it is an irrational system, but my ultimate beef with our fetishization of homeownership in the US doesn’t spring from some series of economic inefficiencies. My beef, rather, comes from the fact that the whole rotten system is pure evil, in a moral and a spiritual sense. I don’t mean to say that owning a home is evil, and I certainly don’t mean that anyone is evil because they own their home. I do mean, though, that a system that says the surest way to wealth is through homeownership while locking the poor and the black out of that process is evil incarnate. I do mean that allowing suburbs to lock brown bodies out through tricks in their zoning codes is evil incarnate. Funding schools based on property taxes while not allowing the poor to move in is evil. Plundering the US Treasury to pay for the mortgage interest deduction which goes to the wealthy is evil. For all the time I spend talking here about efficiency and what makes sense, that’s not where the fire comes from. Rather, through the writing of people such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, I’ve come to see that the US’ housing policies use the power of the state to do violence against communities of color, and our lack of regulation allow private financiers to ravage them further.

We can have all the Ed Glaeser and Richard Florida propaganda we want. We can go read City Lab and learn about what cities are putting in bike lanes and how modern architecture does or does not impact your mood. At the end of the day, however, the problems don’t go away. The rich and the powerful and the white are pillaging communities of color, and our blind fealty to market mechanisms means that these thieves don’t fear a response from the government.

It seems that whenever Ta-Nehisi Coates is interviewed he’s asked if he’s hopeful, and he always gives the same answer – he’s not your guy if you want hope. Of course, if he wasn’t hopeful at all that things can get better, he wouldn’t be fighting so hard for them to change. But I’ve always appreciated his unwillingness to pretend that things are better than they are. What do I think? I’m not really sure. I don’t know if, politically and morally, we have the strength as a nation to start to dismantle these systems that carry forward the legacy of slavery into the twenty-first century. Frankly, I’m not sure that we’re willing to make the sacrifices (myself included) that are needed. I do know, though, that hope is fickle, and can be its own worst enemy. To name the problem and to express hope in the same breath is to minimize the scope of the problem: “we’ve used state violence to subjugate black communities for half a millennium in this country, but we’re so close to getting it fixed” is a statement that falls like lead off the lips. In all likelihood, fighting for justice in urban issues is a fight that will never be over.

Ultimately, it’s not a question of facts and figures and rational arguments. As Coates said in a conversation with Ezra Klien in October, this isn’t a conversation to be had over drinks, casually and without risk. It demands an emotional response, it demands imagining that your grandfather was denied the opportunity to move into a white neighborhood, that your brother was locked up in a cage and denied employment opportunities for the rest of his life for doing the same things that happen every Saturday in every frat house around the country.

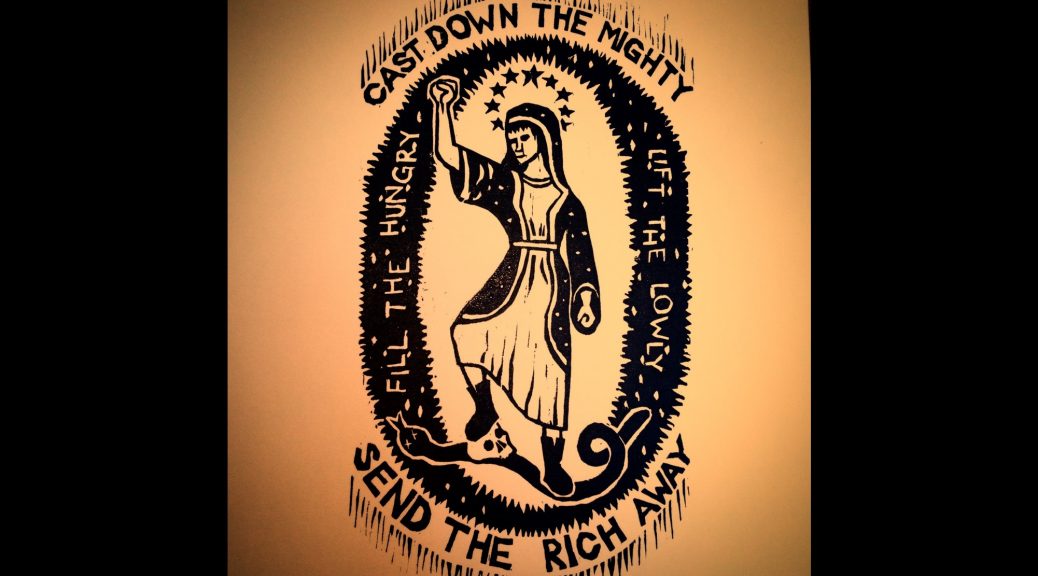

This week, in my faith tradition, we’re celebrating something truly incomprehensible. A little brown boy, born in a Middle Eastern country in territory occupied by foreign powers. Today, the corollary might be in a neighborhood that’s been totally abandoned by the state, his father locked up for nonviolent offenses and his school in shambles. In Christian theology, we don’t think it’s a coincidence that God entered into creation as someone in a deeply oppressed community: that’s the whole point. Most white people in this country happen to call that child God. If we take that seriously, we need to let ourselves stand convicted of great violence in our country against our very god.

But really, thanks for reading, friends. Thanks for being in conversation with me over this year as I’ve continued to wrestle with what I think is just, and thanks for disagreeing with me and pushing back and asking me to look at things in a new way, even when I haven’t changed my bull-headed mind. I’m looking forward to continuing the conversation as we move into 2018.

It’s a vacation-ish week for lots of people right now, so I’ll also recommend listening to Coates on Ezra Klien’s podcast this fall. It’s really, really, really great. Go listen.

* I say “roughly” because around the same time I was also reading Melvin Oliver and Thomas Shapiro’s Black Wealth/White Wealth, Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy, and others, though those didn’t have quite the same world-opening impact on me.